Cara, Udio and the Stone Temple Pilots

Untangling the vanishing middle in Fair Use and "paying for inspiration" discussions

So here is what Meta are trying to pull over at Instagram, which has already had half a million of their — and Twitter’s, and ArtStation’s — users bail ship for Cara over the last few days. It’s also why photographers and illustrators on Adobe Stock are angry at Firefly, and why Sony wrote that open letter to 700 gen-AI music companies.

The post is based on a rather good online discussion about Udio with Steve Stewart, CEO & Co-Founder, Advisor, Former Stone Temple Pilots Manager who was a great sparring partner. He kindly supplied the full transcript below in comments.

This covers my best attempts at adressing some rather tired misunderstandings. Edited for clarity.

Human vs Machine learning/inspiration

N.N: “We’re all inspired by what came before. AI learns like people, so why should I pay? I’m just using a tool.”

You’re a person.

You compare mass statistical processing of billions of specific song recordings on a data center for hundreds of thousands of dollars to the embodied, encultured, reciprocal, dynamic, living process of human learning that takes in a myriad of different sources.

When actually composing and producing a song, you consciously arrange each element. If you emulate a pre existing song, you most likely do so consciously. If you want to borrow a sample, you clear it. If you do a cover, you credit the original songwriter. And when you perform it, it expresses your personality: your limitations and idiosyncrasies as a performer, your choice of instrument, acoustics, effects. Your subjective interpretation of the emotional resonance and meaning of the song.

Whereas an AI model is nothing but samples. A statistic compilation of underlying works, from which you can extract derivatives.

There is no similarity at all.

Not ontologically, not technically, not legally, not morally.

Commissioning vs Authoring

N.N: “A lot of inspiration is unconscious. Covers are intentional and should be credited. The issue is how much does an AI generated song sound like another song?”

When you prompt a song from an AI service, it doesn’t express your personality, but all of the personalities expressed in the underlying musical recordings, filtered through the model and algorithm.

You commissioned content from an automat. You did not author a work.

The value of the service comes from the model. And the value of the model comes from the underlying works, which were not licensed.

Model makers and service providers are keen to anthropomorphise their service by way of PR to muddy the legality of licensing.

But really, while machine learning is designed to mimic a subset of brain functionality that makes up one aspect of human learning, the likeness in practice is no closer than between a human running and an engine running.

We can explain metabolism in terms of “burning” “fuel” but it’s just a figure of speech. Our common sense and intuition based on experience tells us that there is an ontological difference between the technical and biological domains —that the dead and the living play by different rules in terms of pure function. We can therefore intuit that the living being and the machine are not morally equivalent: one has only instrumental value, whereas the other has inherent value. Dead objects serve must serve living beings. And on that moral ground, laws are built.

This intuition will eventually develop at scale for the less visible and tangible technology of AI, but tech PR isn’t helping; both educational material, tech explainers, marketing and even legal pleadings lean heavily on the anthropomorphisation crutch.

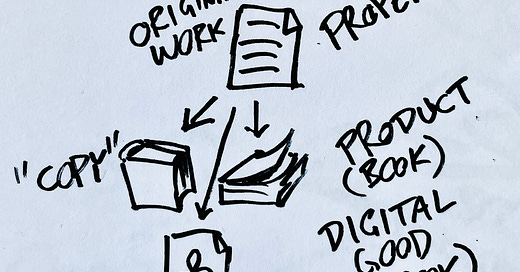

Authorship rights vs “copyright”

N.N. “Does a writer express their personality when they write a story? And should every artist have to pay every artist that came before them, as they trained on and were influenced by their work?"

The same principles apply across the arts. A work of authorship is made by freely and creatively composing elements in a way that expresses the personality of the author. This is the legal basis of copyright.

“Copyright” is an unfortunate misnomer in the english-language vernacular, as it mislabels the wider bundle of rights that spring from authorship through “concept creep” — extending the narrow example to cover the whole category.

Authorship rights or origin rights, as its called in many non-English languages, more intuitively captures the full basket of rights, that covers not only reproduction, but also distribution, performance, playback of recordings, adaptation and preparation of derivatives such as translations (source).

You own what you make.

You pay for the rest.

You ask before, and you credit after.

Really. It is that simple.

Adaptation and derivative rights are the most pertinent to generative AI, as scrapers will target sources of quality copyright works and grifters will prompt or upload works to spit out summary books for Kindle, knock-off works for Etsy, etc while spouting “can’t copyright style”.

This was true enough under the assumptions of the previous technological paradigm. Not so any more, when style has been productised and is easily machine reproducible.

One can only wonder how many downstream misconceptions stem from representing the legal concept of “authorship rights” by its specific application to mass copying, rather than the underlying rationale of authorship and originality. Might a change in label help facilitate copyright’s transition to the new era of mass machine origination and push-button style transfer?

For one thing, we would at least stop hearing the false meme of “copyright is just about copies”.

Inspiration vs sampling

N.N. “Sampling — using an actual piece of a master recording, however small — is an infringement. Influence from thousands of songs over many years is not.”

Arguments like these to me sound like tinmanning — reducing the highly subjective process of authorship to statistics, or worse, an attempt to reduce the author to a computer.

Your myriad aesthetic choices are always-only yours, in the end. There may be a lot of influences, but the intent, the idea, the execution and the editing all express your values, your will, your life experiences as a living human being.

When you write you can also come up with original ideas, and novel expression of timeless ideas that resonate with an audience. Because every choice you make in producing your work is a result of your intent, will, judgment, values, aesthetics, ideology, politics, sense of humor, quality, relevance, in connecting to other human beings.

None of which is present in a statistics engine, except, well, statistically.

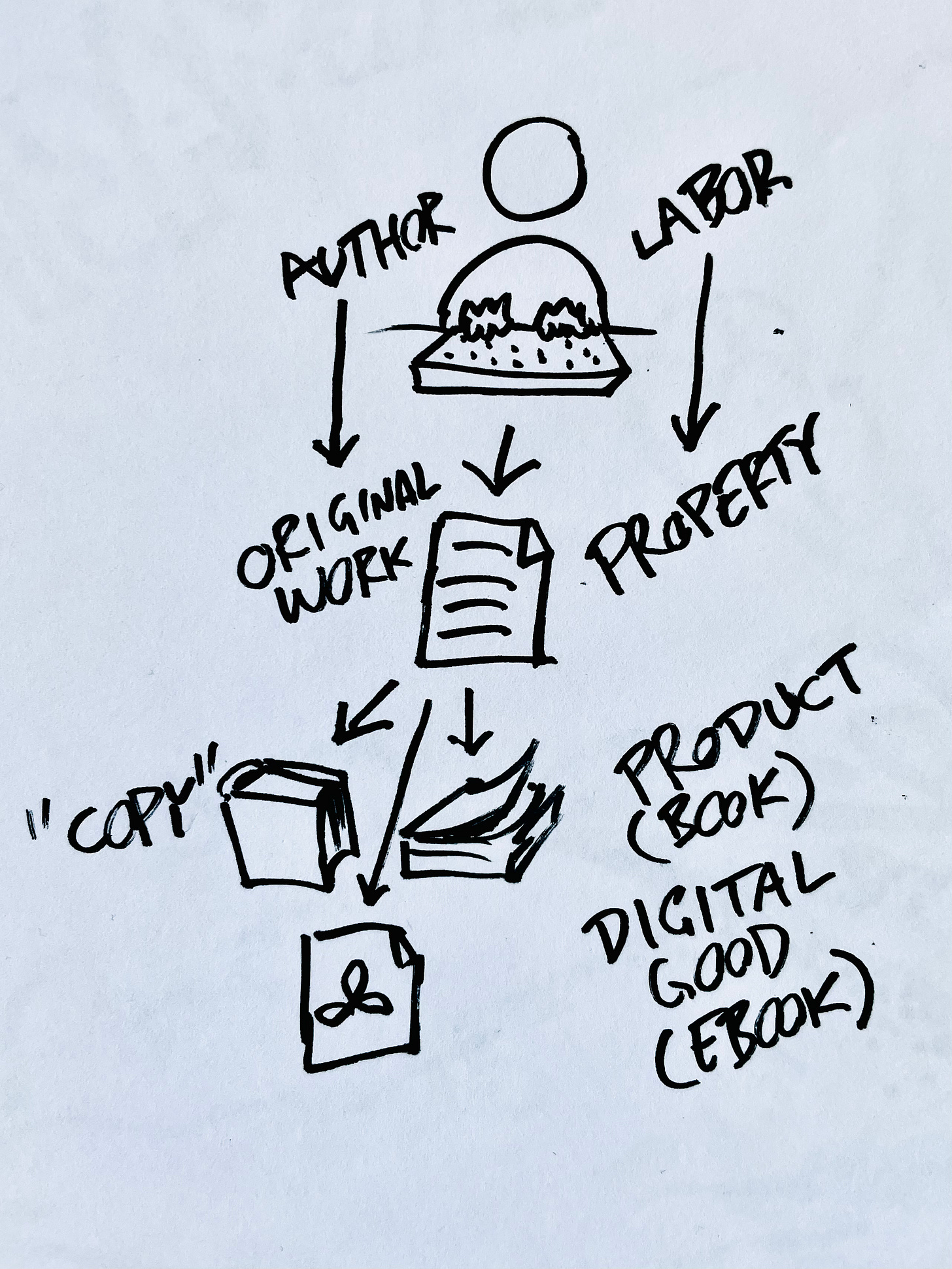

The pizza glue incident showed clearly that language models have no clue about any of those things.

The vanishing middle fallacy

Let’s use the pizza glue example to disentangle two relations that are often unproductively stuck together. Online debate often frames this as prompter vs author, a direct relationship between craftsmen on equal footing — the end-user of AI vs the unwitting supplier of training data. This is a major leap of logic, as we have two wildly asymmetric relationships hidden in between:

a relationship between a billion dollar company and millions of authors of underlying copyright works, which should have been licensed,

a relationship between a user and a service provider that sells derivatives of their work to you under the pretense that you made what they sourced and produced for you.

This is where many Fair Use discussions get stuck. Because it’s not about single individual user outputs vs single individual copyright works trained on.

An AI model is a storage format. A lossy, interleaved storage format of latent media data, indexed on labels. When we say it “learns” “concepts” by “training” it really means we store the expressive content and index it in a way that can then later be retrieved. Functionally, it’s “just” storage — only not one-to-one, but many-to-many for the purpose of doing many-to-one. (Yes, there are lateral use cases of generative AI models too, out of scope here.)

Prompting is then clearly not an act of authorship, but of approximate retrieval. Credit to Subbarao Kambhampati of AAAI for putting it that succinctly.

The part you can claim authorship of is the part you directly control: the prompt. You made the prompt by typing each letter. You can try to copyright it. By the same standard as any other work of authorship: it has to exhibit a modicum of originality as well as be an expression of your personality through your free and creative choices, in its own right.

Fooled by randomness

So the model is a vast repository of preexisting but latent recombinations of granular elements of the expressive content in the training data (media) indexed by way of the keywords in its metadata (text labels).

You send your prompt text string to a service that processes it by re-calculating it into retrieval coordinates.

A pseudo-random seed is added so that you get a “new” output each time you send the same retrieval coordinates; send the same seed, get the same output, save for some rounding errors.

Many services accept more advanced inputs, similar to how you might submit reference photos to an illustrator, a manuscript to a translator, or a deeper Q&A for a contractor brief.

Your prompt supplies an idea and some direction in the form of prompt words or other parameters, and the AI service serves an expression of that idea made from content stored in the model.

The unit of a Work in copyright law is comprised by two parts: an idea and its expression. What you did here is, you supplied half, if that. The AI service provided half, and the underlying work provided most of the value, via the model — with a nominally unique twist, because of the random seed, and potentially tweaked according to your additional inputs.

This is why the USCO have reiterated in numerous registration attempts that genAI output is not copyrightable. In their words: “you’re not an artist for finding a pretty stick in the woods”.

Style as a product, served with a mankini of deniability

As the statistical processing is multi dimensional, and as music is math on multiple levels, and as all media are stored mathematically, the “AI” can “pick up” on a “style” by extracting and recreating subtle mathematical patterns. (Again, this is an anthropomorphised simplification.)

The artistic style of Stone Temple Pilots can be extracted from Stone Temple Pilot recordings — insofar as it is consistent across the recordings used as training data.

When you type “Stone Temple Pilots” into Udio, you may have noticed it won’t let you refer to artists directly. But since your prompt is numbers, as per above, Udio can easily “infer” your intention and suggest an alternate string of keywords that will yield a coordinate close by to not make much difference in terms of outputs. It will even give you those keywords, and the output, with a nudge nudge wink wink.

This serves to sustain the “tool” illusion, and exhibit a mankini of deniability for copyright infringement. Users get to spam their royalty free “90s alternative rock, grunge hard rock, alternative rock, melodic” track across their socials and marketplaces, Udio sell subscriptions, and they can both together cite the flimsy double-yet-incompatible excuses of “It learned like people” and “I made it by prompting”.

Fair use without the vanishing middle

So what is really going on here, in terms of Fair Use? Let’s break it down, after the mandatory IANAL disclaimer:

I Am Not A Lawyer

My credentials are having worked all sides of creating and licensing international IP and commercial art way back when, to then move into business development and innovation of data-driven digital products and services. I’m a cartoonist at heart, working at a tech consultancy, figuring out how to monetize data while using tech as a means of visual storytelling – often to market and explain tech.

The Amount Factor

We have a company, a multi million dollar venture which has copied millions of song recordings and compressed their expressive content, the media content of those files, into a model.

This in itself is theoretically legal, although let’s be real here, there is no way to legally obtain millions of tracks without involving at least one music publisher at some point in the process. (And also let’s be real that the entire AI boom is powered by the hopeful assumptions by investors of a credulous and entitled user base who believe this time it really will be free forever, clueless and/or powerless regulators and a metric fuck-ton of lobby money.)

The Fair Use factor here is substantiality of portion used. The play is to mince the content down into small enough bits that no one track going out is too similar to any one track going in. But we can’t get stuck on the level of a single work. Substantiality here dwarfs single songs. Even looking at the total lifetime output of one producer or artist, or the entire catalogue of, say, Universal Music Group, the substantiality is “all of it and then some” in terms of quantity and “enough to produce market replacement level derivatives” in terms of quality; good enough for Wish is bad enough for lawsuits.

Or in the words of the Berne three-step test used when ruling international copyright disputes: it interferes with normal exploitation of the work.

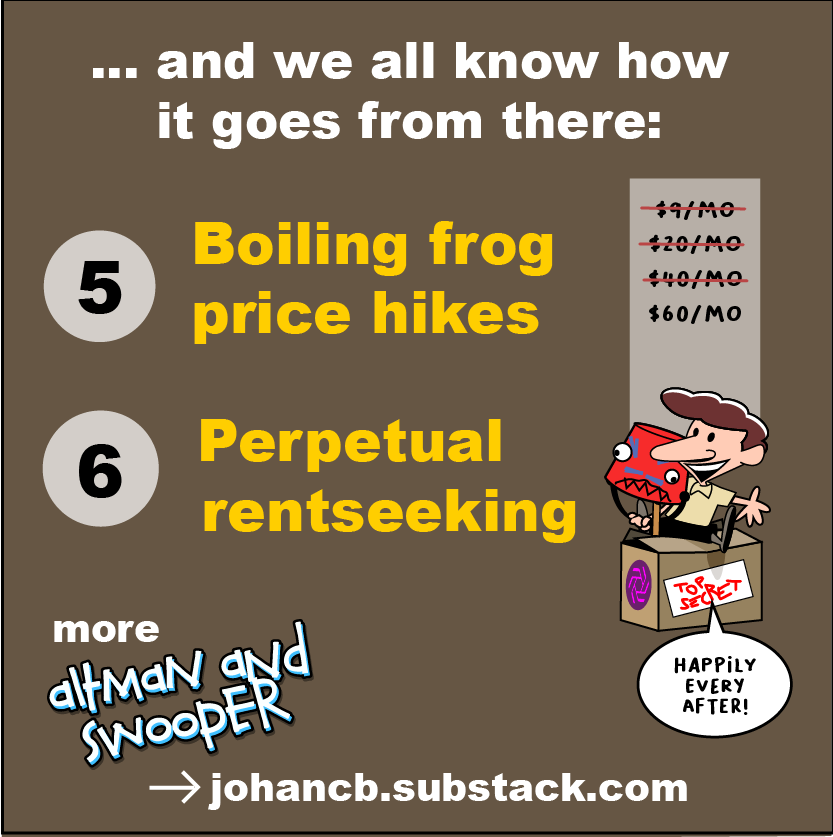

The Purpose And Character Factor

Udio then rents out access to this model, offering it discounted to the low, low price of nothing — except your training data (your prompts and other feedback used to refine the algorithm) and the advocacy I’m sure to receive in comments.

Until they’ve established market dominance, after which we all know prices are going to get gradually jacked up forever.

This is not a scientific research project run for the betterment of mankind and the noble cause of democratising creativity (lol). They want to get you hooked on this new more convenient way of making and listening to music. They compete directly against all of the music industry as is: the recording studios, the artists, the labels, the streaming services. Udio extracts value from all of them, by way of the copied recordings and the model of those recordings and their metadata.

The Market Effect Factor

So we have replacement derivatives that compete against the originals for time, attention and money. In other words, they redistribute value from the creators and rights holders of the original songs to developers, service providers, investors and users.

When new tech rams arts like this, courts look at precisely this: does this bring new value, and if so, does that interfere with existing marketplace value? Google Books is a prime example: they pay for the snippets they display, as reading free samples arguably takes away from reading the book. But as for Fair Use, they do not provide a service primarily for distributing and reading books (unlike direct piracy sites) — it is for searching for books, and promotes discovery by way of ads, which arguably offsets the market effect of the free samples. (Google also “train” “AI” on that corpus, but that’s another can of worms).

The Transformative Factor

So what Udio do is, they promote their service as a music creation “tool”. Which makes gullible and/or entitled users argue as if prompting a song is just like picking up a guitar or Cubase and a sampler.

Despite Udio doing the work for you which makes it a content production service that you commission outputs from, not a tool with which you make the outputs yourself.

This neatly misdirects the “transformativeness” discussion towards one of original-to-derivative / input-to-output similarity at the level of the Work, and deflects from the more glaring issue of non-transformative use at the service level. Such as Stability.ai flipping over viewing copies of stock photos from Getty via their open source model into a for-profit service that functionally replaces the original service. Or of Adobe sourcing Firefly images from their Stock service to openly bypass their own Stock contributors and sell replacement derivates of their works otherwise licensed to customers.

Cubase and Yamaha aren’t likely to sue Udio for making a better tool. One, because it just isn’t. And two, because it’s not based on their property.

And let’s say they ripped all the tracks off Spotify — incidentally also very much founded on piracy and still not legally off the hook — they aren’t going to sue, because Udio exploit the author’s right to prepare derivatives, whereas Spotify exploit the right to distribution.

Those who will sue are the artists who wrote and performed the songs, and the music publishers who own most of the recordings.

“In conclusion…”

The way to frame Udio’s misdeed is that they process unauthorized copies of unlicensed original works to compete directly against their authors and other rights-holders in the marketplace.

Just like OpenAI and Midjourney kicked off with, Adobe and Firefly were quick to imitate, and Meta are going for. Silently and unilaterally expanding the license you gave them of your exclusive, by-default lifetime right to distribute and publicly display your works, to also claim your rights to prepare derivative works.

But a new business model and a new claim to commercial exploitation rights means a new negotiation.

It can’t be imposed silently, unilaterally or retroactively.

Which won’t stop them from trying.

But that’s just good ol’-fangled piracy — dressed up as a porcelain terminator in the public imaginary, supported by a one-way railway to the future mindset by investors, pilfered from the back pocket of professional creators and the general public by model builders, and served as The Next Big Thing by credulous users.

Which is why you should consider switching to Cara right now — or even give that whole “internet” thing a miss for a bit.

Post script

Fair Use and its four factors is a very American thing. Most countries instead have a set of narrow exceptions, under the rubric of Fair Dealing. This arguably provides Americans with a greater flexibility to innovate.

In mediating between sovereign states with different copyright law, international treaties on IP and indeed developing AI/IP law around the world instead converges around a similarly simple framework, called the Berne three-step test. A subject for some future post.

Post post scriptum

By lucky coincidence, I happened to address some of the more egregious nonsense coming out of newly minted Big Tech lobby group “Chamber of Progress” — launch eerily timed with tech philosopher Daniel Schmachtenberger’s new paper on moving from naïve to authentic progress, here outlined on Nate Hagens’ podcast. Highly recommended listen!

It's extraordinary to me the relentless lack of critical thinking and understanding of how these models work that's being exhibited upon the wider Internet, in relation to generative AI. Always appreciate your thoughts Johan.

I know Glaze and Nightshade exist for protection of human- made images, I hope something can be created to also protect music and writing from being illegally scraped too.