Picasso should have read the ToS

Some notes on a flawed gotcha

The Verge just published an impressive overview of all the creative excuses from AI companies to the USCO to not have to pay for the property they’re built on. It’s an absolute blast, go read it. Then come back here and drill down on one of those lines of reasoning with me.

A recurring comment in the Prompters vs Artists debate that doesn’t seem to go away is “Shoulda read the ToS.” While the cynicism towards platforms is absolutely justified, it exposes some remarkable assumptions:

Generative AI companies licensed their training data.

They do so from platforms with rights to sell it.

Material was uploaded by creators or rights-holders in the first place.

Let’s go over each of these in order.

1. Licensing training data

How about nope?

The generative AI startups who reveal their sourcing so far at best gesture at potential future licensing and claim “transformative fair use” to explain why they don’t. Big Content actors like Shutterstock, Adobe and Getty have all launched image generator services with “ethically sourced” as a selling point for this very reason.

The high-falutin’ version of the argument, as set out by OpenAI in their comment to the 2019 USPTO RFC on AI and IP goes, generative AI is the sort of radical leap copyright law was set out to protect in the first place, and generating new content is a fundamentally different purpose than that of the underlying works, which are for human consumption.

Now while that may hold true for the directly derivative use, the entire point of the exercise in the first place is to produce second-order derivatives that substitute directly for the source material — all the while quoting them liberally. Yes, there are also other, lateral uses that do bring novel value. But the core use case is to produce remixes of the source material.

The more direct version of the argument – as being tried in court – goes, as single particular outputs do not infringe on single particular underlying works, no chargeable offence has occurred.

What has been ingested here are entire bodies of works — entire lifetime accumulations of cultural capital that functions as marketing material and sources of licensing revenue. In order to output infinite, almost-free imperfect almost-copies that, as amply demonstrated this past year, destroy the market for the underlying works by radically dumping prices, substituting for commissions and directly competing for share of search results, display windows, wall space and — wallets.

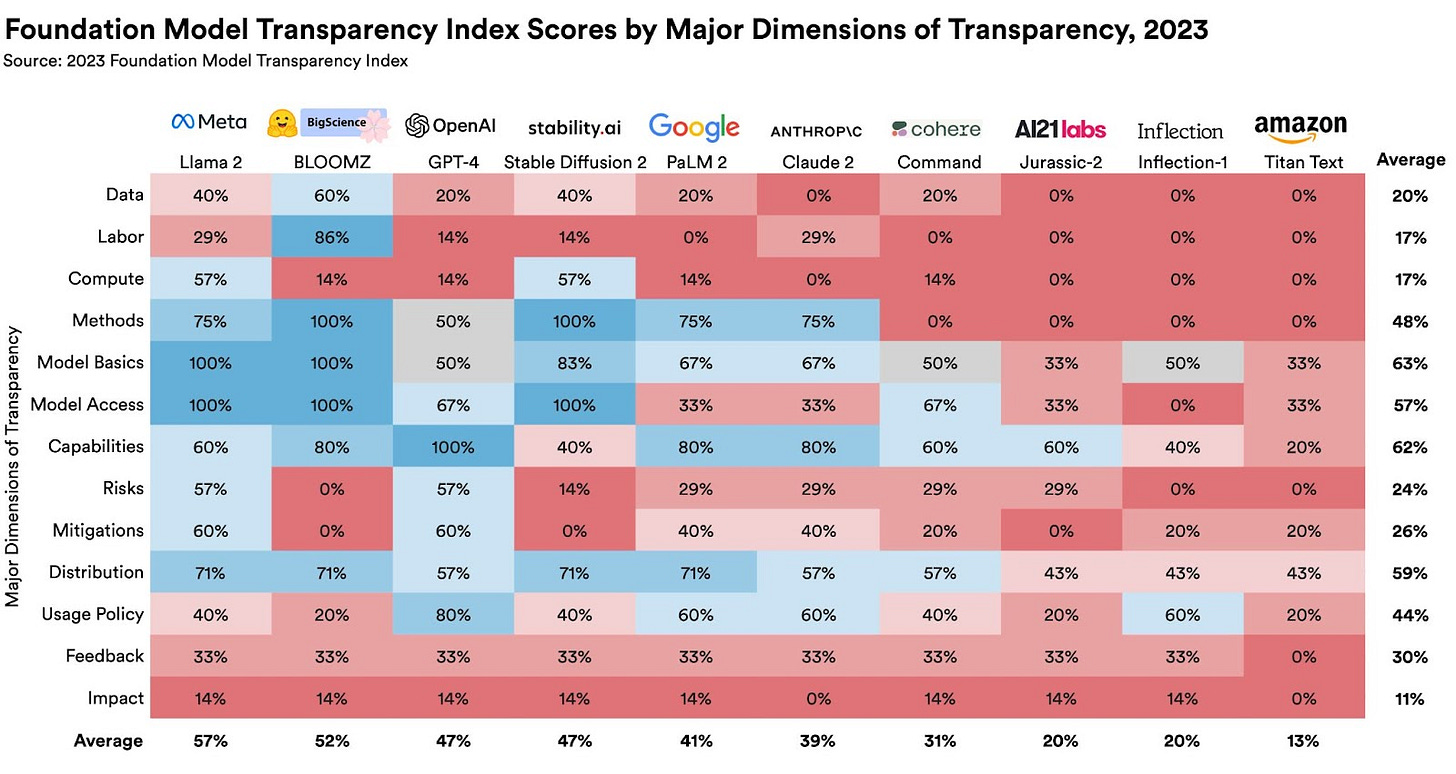

Prying open AI black boxes

A few AI players claim to have licensed their material, but well over a year into the generative AI boom the black boxes remain shut, and to my knowledge no data sellers have come forth.

AI lobbying has been successful in staving off data transparency requirements from both the Biden Executive Order and the G7 volontary Code of Conduct and guiding principles announced this week. Meanwhile, rights-holders in the EU hold out hope that the AI Act trilogues will retain the requirement for summary disclosures of copyrighted works used as training data.

Ongoing regulatory action, such as the FTC probe opened in July against OpenAI for deceptive business practices, does investigate data sourcing and offers hope to US rights-holders in testing applicability of present law on these nominally novel systems.

And among the USCO Request for Comments on AI and copyright, which yielded nearly 10K comments, can be found some hard-hitting research by rights-holder organizations on the amount of source material that carries over directly into LLM outputs from training data.

Pending all this, one would-be data seller after the other has taken generative AI companies to court, or announced their intention of doing so after negotiations stranded.

A quick look at data pricing

To understand where we are, it helps to have this quick look at how copyrighted works, training data and model outputs are currently priced.

Stock libraries like Adobe and Getty license images to end-users for limited use at $100 and up. Online display for commercial use starts at $300 per image, per year.

Buying the same image as AI training data scraped from the web starts at $0.01 per tagged image for bulk sourcing of a mixed bag.

Licensing the same image from the seller, who in turn licenses it from its creator, costs $1-10 depending on niche and quality. (source)

Exclusive data such as artistic works or celebrity faces are usually licensed on a revenue-share basis, starting at 50% royalty.

Stability.ai sell images from their research models(!) at $0.002 per image. (source)

Midjourney’s pricing model is based on GPU hours rather than number of works, so does not invite easy comparison. But a rough back-of-envelope sketch: $10/mo for hundreds, $120/mo for thousands ≈ $0.05–0.10 per image. (source)

And Adobe take the cake. Where they previously pocketed a difference of a whopping 100x on Adobe Stock (licensing images at $100 to customers while paying out $1 to Contributors), they started selling non-copyrightable AI outputs at the same $100 list price to customers, and forced all 160M images by existing Contributors onboard as training data for their own Firefly service, without prior notice or opt-out, at an as-of-yet undisclosed price point entirely at their discretion. Expect an outcry from Contributors when initial payouts are due within the coming months.

So while AI imagery comes with oftentimes worse quality, a lack of creative control, and no legal protection besides indemnity offered by vendors (unless you set up shop in the Ukraine, UK or India), it’s a booming business if for no other reason than outputs are priced below inputs.

This is only achievable by either subsidizing outputs or underpaying for inputs. While the former is standard Silicon Valley startup strategy, this is not what we’re dealing with here.

And when would-be licensing negotiations begin four orders of magnitude apart, sitting down at the table makes little sense. So off to the courts, the legislators and the court of public opinion we go.

2. Bulk licensing from platforms?

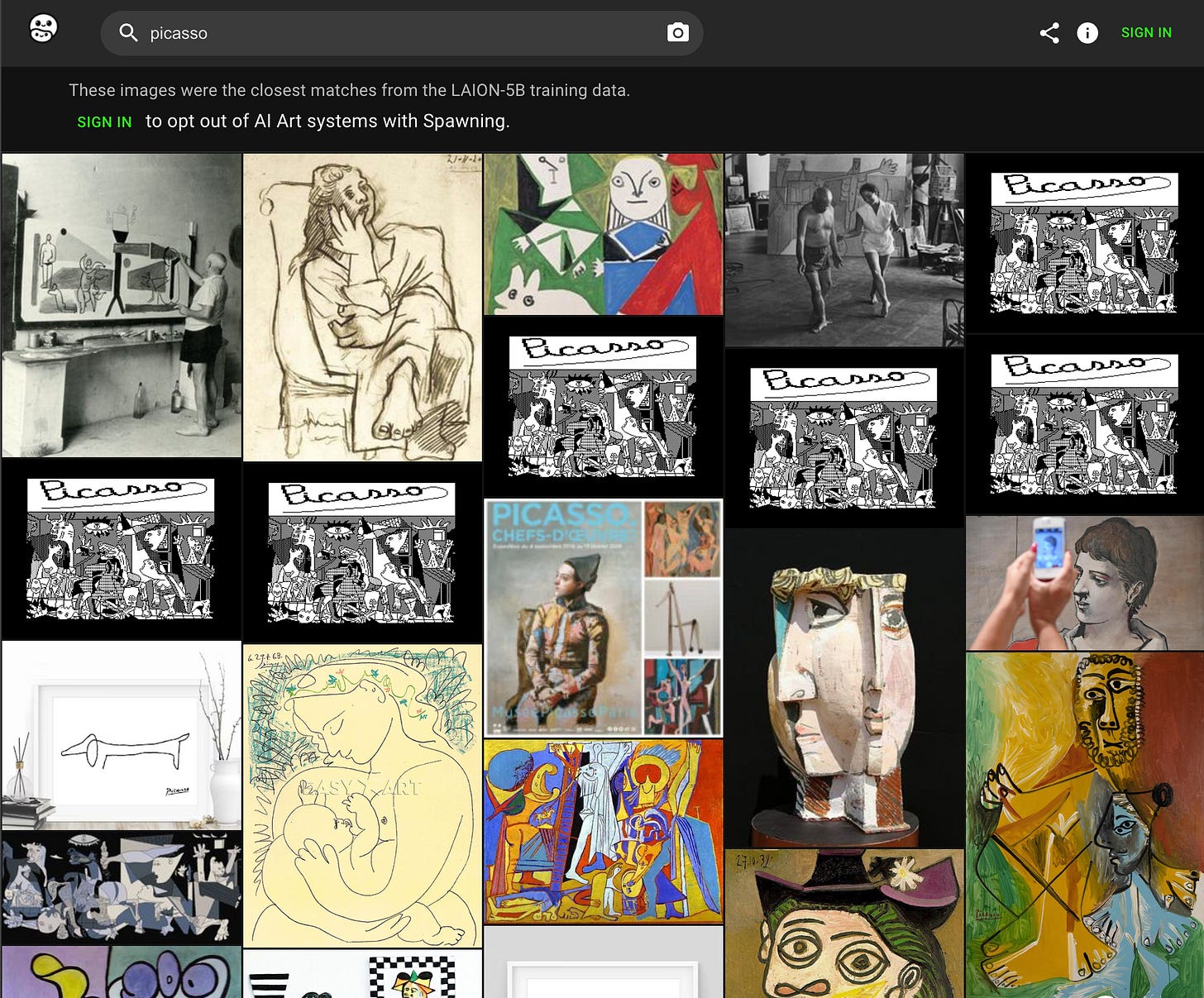

All training data are not created equal. Both images and descriptions need to be of good quality. The top source for prime Stable Diffusion training data is the LAION-Aesthetics v2 5+ dataset of 600 million images, released August 2022.

Some top categories there are

55M+ from e-commerce sites, such as Shopify, eBay and PicClick

40M+ from stock sites, such as 123RF, Dreamstime and Getty

10M+ from news sites, such as Daily Mail, The Star, Fox News and The Sun

6M+ from art and photo sites such as SmugMug, Flickr, ArtNet and TopOfArt

~2M from portfolio sites such as DeviantArt, Dribble and Behance.

Source: Author’s own analysis. Reach out for details.

What all of these have in common is, they are sources of curated, labelled, professional quality images, either licensed for specific uses or put on display as marketing. While the long tail of two billion randomly scraped images includes all sorts of unsavory content from a privacy, safety and decency perspective, training is weighted 90/10 or more towards the above quality content – so ought to entail a corresponding difference in licensing price.

As soon as the above data sourcing practices became known and it was possible to do so, Haveibeentrained.com collected over one billion opt-outs from AI training within six months. Stable Diffusion v1.5 and 2.1, both based on this body of data, are due for retirement Nov 15th. But only after having sold untold millions of generated images and spawned dozens if not hundreds of commercial services, and only to be succeeded by Stable Diffusion XL, which is still based on opt-out rather than a reasonable opt-in of copyrighted works.

We will see why opt-in is the only reasonable data sourcing method in a bit.

Also note that these were not sourced via social platforms. But as soon as Stable Diffusion took off, every collector site, stock site and social platform rolled out new terms of service to permit such use; all retroactively, many covertly or post fact, all with sweeping statements for future technologies, and all with no or broken opt-out systems.

Which brings us to our final point:

3. Where art comes from

If I post infringing content here on Substack – whose problem is it?

Like all major platforms, Substack leans on the Digital Millenium Copyright Act (DMCA) and their own Terms of Service (ToS) to manage liability. In addition, they have a copyright dispute policy, a repeat infringer policy, and reserve the right to remove or block infringing content without prior warning.

In short, it’s not their problem as long as they follow protocol. Which goes as follows:

Rights holder or representative files a DMCA Takedown request, providing a source link.

Platform takes down infringing content and notifies alleged infringer.

Alleged infringer is allowed 10 business days to file counter-claim.

If the claim was faulty, the content is restored.

Substack’s incentive to comply is to keep their Safe Harbor status, meaning immunity from infringement claims. Under the DMCA, ISPs and platforms offload liability by positioning themselves as a neutral intermediary in-between end-users, rather than a publisher.

Voices are being raised for revising the DMCA lately, but for now, them’s the rules.

Now let's look at what that means for artists:

Pablo’s problem

Picasso, Picasso, Picasso… Iconic artist dude. Body of 45,000 works.

Did he study the ToS? Does he use the DMCA? Pfft! Instead he went on this wild posting spree:

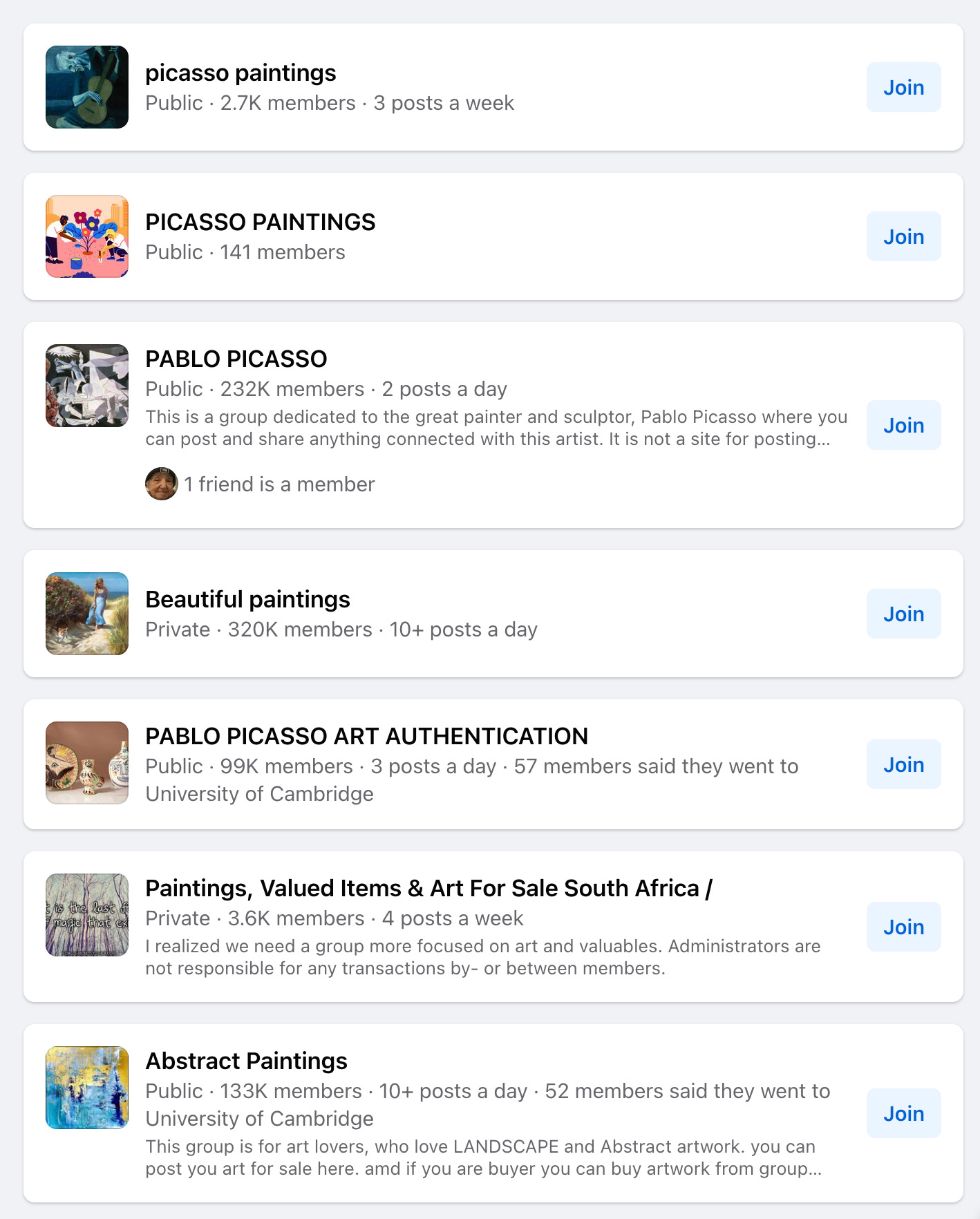

That absolute floozie. Single-handedly spamming every art group and collector site.

Despite being dead for 50 years.

And so he got his just desserts:

Checkmate, paint pig!

Enjoy your free ambassadorship for artist replacement services:

To make your style more specific, or the image more coherent, you can use artists’ names in your prompt. For instance, if you want a very abstract image, you can add “in the style of Pablo Picasso” or just simply, “Picasso”.

– Dream Studio prompt guide; section 3: Artists

So what is the lesson here for our beloved promiscuous zombie artist?

The DMCA flipped the onus from online publishers onto every rights holder to police their entire body of work across the entire internet, all of the time.

The definition of a popular work is, it gets shared. By fans. Outside of the artist’s awareness. From sources outside of their control. To areas of the internet they don't have access to. And T-shirt bots.

You weren’t a subscriber to that particular newsletter? LOL take the L

You didn’t infiltrate that closed group? Ya snooze, ya loose!

You weren’t on that platform? Game over, artcel!

You weren’t even on the internet? Adapt or die!

Your work belongs to every platform and their scrapers now.

If I post infringing content on here, and it gets taken down by the rights-holder – so what? My subscribers already have it in their inboxes. And I can take it to any other platform. The internet is a place of infinite copies — always has been.

The DMCA became law in 1998.

The whac-a-mole has been ongoing since.

Survival strategies for digital native artists are many: paywalls, subscriptions, commissions, merch, crowdsourced projects. Meatspace scarcity, early access, exclusive access and loyal fanbases can all be monetized. But the open internet and major platforms were only ever for marketing. And as policing the internet was a fool’s errand and going viral used to mean hitting the jackpot – why bother? DMCA:ing largely didn’t make economic sense.

And as for whales, like The Picasso Estate who manage his rights for another 20 years, there are several tools to automate parts of online rights policing. But even with fully automated processes, it’s a constant arms race between exploiters and defenders, with many of those training data sources out of reach.

Now run the above dynamic for 14 years, and what do you get?

Training data sets full of copyrighted works never posted by the rights-holder. Often despite their wishes and attempts at content protection.

And this cold shower for artists:

Your works are literally everywhere.

Everything anyone ever posted of your work has been turned against you, as price-dumping, porn-spewing remix machines.

The more successful you were, the more efficiently you can be replaced.