Sam Altman and the Sorcerer's Stone, part III

In which we break the spell, and look towards the future

Originally published on LinkedIn on the same day as the two new class action lawsuits against OpenAI — one from the public over privacy, one from authors over copyrights.

Part I • Part II

Flight of the bumble-owl, explained

At this moment we must briefly freeze-frame and retrace this investigation, and the steps that led up to it, to fully appreciate the dazzling logical and legal acrobatics on display. Let’s see which of the many impressive spells you recognize from the last several years, and the fierce PR push of this last year:

Copyright somehow doesn’t really apply on the internet.

If anyone ever uploaded your stuff, it’s not really yours anymore.

Appropriation of copyrighted works while ignoring rights and attribution information somehow isn’t really theft.

Hosting civilization scale collections of pirated content from others somehow isn’t really piracy.

Any terms of service you ever agreed to weren’t really limited to what tech existed at the time and the commercial arrangement then undersigned.

Their company somehow isn't really a company so much as an academic-exemption-from-compliance-sounding "Open research lab" or some such.

Their product somehow isn’t really a product.

Lossy storage somehow isn't really storage.

"Training" somehow isn't really data processing.

Processing copyrighted content somehow doesn’t really make up most of their product value.

Content licensing isn’t real, period. Except for maybe mugs and t-shirts.

This time it really somehow is for free – not just until firmly embedded in user habits, business processes and product stacks.

They’re somehow not really claiming your property for free to rent it back to you.

Their billion-dollar valuations somehow aren’t really a bet against your fundamental rights.

– Presto! Expialidocious! Alakazam! Macramé!

Publishers are no doubt in intense backroom talks over this evident rights-grab since the last several months. According to Schoppert's research outlined in Parts I-II, Penguin books alone are represented with over six thousand titles; it's anyone's guess if a top publisher or some broader coalition will sue first. Or, as is the case with image generators, both of the infringed parties: creators of the works and their present licensees.

They will have to get in line though – after both developers, the U.S. public and the authors.

Conclusion: a culture of piracy – and its responses

If our story so far does not already add up to a clear enough sketch of a developer community that hold themselves and their products to be above the law and fundamental rights of others, let’s look at just two more examples to round it off:

Microsoft-owned GitHub were famously first out to be sued over rights-and-attribution-stripping generative AI services, also powered by OpenAI, for breaching an impressive eleven different software licenses at once.

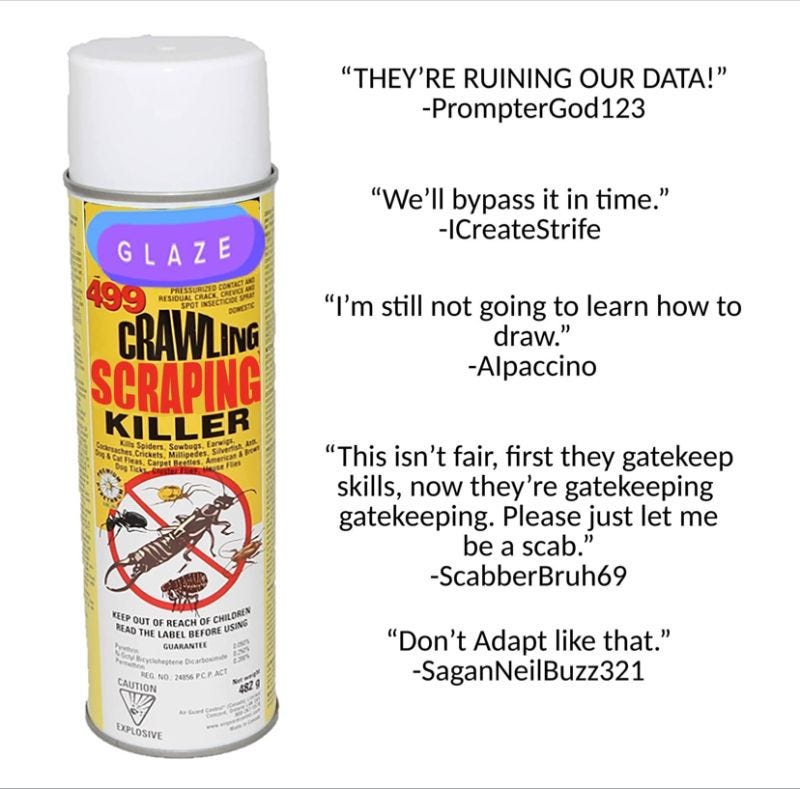

Besides conveniently rounding off “some rights reserved” down to “none whatsoever” regardless what FOSS or CC license came attached (big topic for another time), they also host resources for machine learning, which glaringly include watermark removal and de-glazing. Tools to remove attribution information and copy protection at scale, incidentally legal to use, well -- nowhere?

Which brings us to the proper intro to our final hero of this story: professor Ben Zhao first mentioned in Part II, a brilliant mind and staunch rights advocate since years, whose research team has already helped three-quarter million image professionals protect their work against illicit scrape & train practices by building and providing cloaking software Glaze. This has opened a path for a family of similar solutions set to appear on the scene shortly, following the recent release of Glaze 1.0.

Images cloaked by Glaze are difficult to detect and remove, which makes automated mass processing harder and more expensive. More opportunity created for those $2/h Kenyan taskers, presumably? But crucial work, given that with enough cloaked images in a dataset, whole training batches are rendered useless.

Mass cloaking like this is a sad necessity to be able to retain any copyrighted content at all on the open internet until the law catches up with unethical data sourcing, unfair competition and copyright and trademark infringement from our modern-day adherents of Moloch and conjurers of Golems.

In conclusion, let me echo this recurring sentiment by Emad Mostaque of Stability.ai – proud purveyor of "””ethical and legal””" Stable Diffusion 2.1 based on only a billion opted-out works:

I can't wait to see what the community makes with this.

Legal afterword

Any misunderstandings my own, as IANAL.

Text- and data mining (TDM) enjoys a limited exception from prior consent to the use of copyrighted works for research purposes across the EU as of Jan 2023, according to directive 2019/790. This does not extend to commercial use, or even to research institutes with close ties to industry. It's a narrowly delimited legal carveout, and of course does not trump fundamental rights such as consent, credit and compensation for the use of intellectual property. But that's a long, LONG story for another time.

TL;DR licensing copyrighted works for commercial use, such as a digital content generation service, is a thing. It exists. But unlike bulk downloading, it costs money and is difficult. So now everyone else has to force our precious innovators to do it.

Which brings us back to those two ominous words in the beginning: "lawfully obtained". It's an obligatory precondition for the exception to take effect in the first place. These two words are the only clarifications to actual law that resulted from the entire Napster debacle. Which is why you may want to perk your ears for the many creative wordings in the vein of "publicly available", "openly sourced", "openly accessed", "openly licensed" content and the like from the gen-AI companies you deal with.

© Johan C. Brandstedt. All rights reserved.

Which is incidentally the legal default for original content on the internet, unless otherwise noted. How about that?

This text available for re-publication with advance written permission by the author.